After an extremely busy end of season, I thought it would be a nice idea to do a little diction post on this platform about one of my favorite subjects: Liaison

Blog: Thoughts and Tips From Your Opera Coach

A Look at the Yod a.k.a the J-Glide

A common point of confusion in French Lyric Diction is knowing when to pronounce the -ill(es), -il(s) as a Yod [j], and when do we pronounce this double “ll” combo as just one “l” [l]. There is a method to this madness, and it is not so complicated.

If the term”Yod” or “j-glide” is stumping you, you can check out one of my past blog posts on the subject of semi-consonants to catch up!

First, we should look at when we pronounce “i” as a Yod.

i or ï is pronounced as a [j] when preceded by a single consonant when it is in front of an a, e, o, or eu. Beware: not when it is in the middle of a word -ie- in some verbs and their derivatives or as the last sound of the word -ie.

For example:

Avant de quitter ces lieux, sol natal de mes aïeux (Before leaving this place, native soil of my ancestors), Valentin’s aria from Faust by Gounod

[aˈvɑ̃ də kiˈte sɛ ljø sɔl naˈtal də mɛz‿aˈjø]

In the example above, in the words “lieux” and “aïeux”, the i and ï are pronounced as a glide. Both of these vowels are in front of eu.

But we do not make a glide in the future tense conjugation of verbs like “oublier” (to forget) [ubliˈe]

J’oublierai (I shall forget) also does not have a glide; in fact, the e vanishes in pronunciation. I often hear [ʒubliəˈre], but the correct way to pronounce this word and other words like it is: [ʒubliˈre]

When -ie- is at the end of a word, it is simply [i] unless the composer gave a note value to the schwa, in which case it will be [iə], and we should not hear a glide between these vowels.

il, ill, ll : When do these letters make a Yod?

- il, ill, and ll make a glide when at the end of a word in the following combinations: -ail,-eil, -ueil, -oeil- and euil.

- il sounds as a glide in the middle of words in the following combinations: -aill-, -eill-, -euill-, -ouill-, -ueill- and oeill otherwise, it is pronounced as [ij].

Examples:

Un deuil amer (bitter mourning) [œ̃dœj‿aˈmɛr]

but in the word fille, we add an [i] in front of the glide; otherwise, there would be no vowel in the word: jeune fille (young girl) [ʒœnə fijə]

List of Exceptions:

As anyone who has ever studied the French language or French diction knows, there are many rules to follow, but there are just as many exceptions to the rules, if not more.

When il(s) is at the end of a word and follows a consonant, the i is [i], and the l is sometimes silent and sometimes sounded.

The following is pronounced without an l or a glide.

- gentil (nice) [ʒɑ̃ˈti] N.B: You should not confuse this gentil with its feminine version gentille [ʒɑ̃ˈtijə] which is pronounced with a glide.

- fusil (gun) [fy’zi]

- grésil (hail) [gre’zi]

- sourcil (eyebrow) [sur’si]

The following is pronounced without a glide but with an l

- cil (eyelash) [sil]

- fil (thread) [fil] or fils [fil] (the plural form of thread and pronounced exactly the same as the singular form) and not to be confused with fils (son or sons) [fis], which is pronounced without an l, but with an s whether it be singular or plural.

You could memorize this list, consult a French dictionary for the IPA translation on these more special words, or refer back to this post.

The exception also applies to the ll in the following words and their derivatives:

- mille (thousand) [milə] Derivatives: million, milliers, milliards…

- ville (city) [vilə] Derivatives: village, villageois, villagoise

- tranquille (tranquil) [trɑ̃ˈkilə] Derivatives: tranquillité, tranquillement

If you don’t want to forget, memorize this phrase: Milles villes tranquilles: “A thousand tranquil cities” then you will remember that every word belonging to the family of these three words in French are pronounced as [l] rather than a [j].

These tips should help you navigate the world of “glide or not to glide” when it comes to the YOd and how to avoid making mistakes while singing, or speaking!

My favorite French dictionary online

We don’t always have a dictionary in our pockets, and let’s face the fact that we are in a digital age, no matter how much we love actual books. My favorite French dictionary online is the Larousse: https://www.larousse.fr/ This dictionary has been my go-to since as long as I can remember, it has it all, and the online version is quite good to work with.

Vocalic Harmonization in French Singing

What is Vocalic Harmonization?

Maybe you have heard this term before, or perhaps it is new to you. When I coach people for the first time, it always seems like they are familiar with Vocalic Harmonization, but they are not sure how to use it. It is a term used in linguistics when applying the rhyming of closely related vowels in the same or words that follow each other. It is also known as “vowel harmony”. The practice of vocalic harmonization is most often used in the French vocal repertoire for linguistic refinement and ease of vocal production. Most frequently in French singing, we harmonize [ɛ] with [e] and [œ] with [ø]

For example: “aimer” [ɛˈme] becomes [eˈme] or Heureux [œˈrø] becomes [øˈrø]

As you can see in the examples above, the unstressed, open vowel-sound closes to rhyme with the following stressed, closed vowel, not the opposite. Remember, it is the final syllable that is stressed in French, except when that syllable is a schwa-sound [ə] because a schwa can never be stressed. In this case it is the syllable before the schwa that gets the stress.

les, tes, ses, mes, ces…

the possibility of vocalic harmonization also exists in closing the [ɛ] in short words such as les, tes, ces, etc. (these are articles or possessive adjectives). When a closed vowel immediately follows these, they can be closed to an [e].

For example: les étés [lɛz‿eˈte] would become [lez‿eˈte]

The article “les” is harmonized to the closed [e] in “étés”

These harmonized syllables must never be accented or overly closed, and at times they only are slightly closed on the way to their closed neighboring vowel-sound, and over-closing the harmonized vowel can result in obscuring the text. The idea is that it should feel natural and sound authentic since vocalic harmonization occurs in everyday speech but not deliberately. Many native French speakers do not even realize that they are doing this.

Some French words are almost always harmonized. For example, the following words would have all open vowels in the first syllable if we followed the diction rules, but they are sung and spoken with vocalic harmonization:

aimer (to love) [ɛˈme] becomes [eˈme]

baiser (to kiss) [bɛˈze] becomes [beˈze]

heureux (or heureuse) (happy) [œˈrø] becomes [øˈrø]

Vowel harmonization should not be systematic. It is a completely optional choice left to the singer. In cases where it can help the legato line, it is recommended to harmonize the vowels as sometimes it is easier to get through a phrase with fewer vowel changes.

For example:

Let’s take a look at “Lydia” by Fauré. In this text we find this line: “Laisse tes baisers de colombe”

The “tes baisers” can be sung as all closed [e] but the “laisse”” remains an open [ɛ] because the vowel following it is not a closed vowel.

[lɛsə tɛ bɛˈze] becomes [lɛsə te bɛeze]

Speak it out loud both ways and see the difference for yourself.

I would also go further and say if you have an article or possessive adjective (les, des, mes, tes ses) and the following word begins with a closed [o] or any vowel that has a closed feeling such as [i], [ø] [õ] [y] or [o], you can apply vocalic harmonization.

Again in in “Lydia by Fauré:

“Lydia, sur tes roses joues” you can harmonize the “tes” which would typically be [tɛ] to a closed [te] to match the closed [o] sounds of [rozə]. But, the “mes” in “mes amours” in the same song stays [ɛ] because a closed vowel-sound does not follow it.

Here is the text of Fauré’s Lydia where I will highlight the vocalic harmonizations:

Lydia, sur tes roses joues

Et sur ton col frais et si blanc

Roule étincelant

L’or fluide que tu dénoues;

Le jour qui lui est le meilleur

Oublions l’éternelle tombe

Laisse tes baisers de colombe

Chanter sur ta lèvre en fleur.

Un lys caché répand sans cesse

Une odeur divine en ton sein;

Les délices comme un essaim

Sortent de toi, jeune déesse

Je t’aime et meurs, ô mes amours,

Mon âme en baisers m’est ravie

O Lydia, rends-moi la vie,

Que je puisse mourir toujours!

In this recording of Véronique Gens and Roger Vignoles, you can hear the use of vocalic harmonization as highlightede above.

Try not to over-use vocalic harmonization. Remember, it should not obscure the text, and it should be helpful to the singing. If you are not sure if something should be harmonized or not, ask your French diction coach, or listen to several recordings to see what the consensus is. Just know that some coaches don’t apply vowel harmony and there are differing opinions on the matter. Since it happens in everyday speech, and I have seen it help so many singers in their legato and ease of singing, I generally encourage vocalic harmonization when appropriate.

Thoughts on the French “R” in Classical Singing

The French r may be one of the most discussed sounds in the French language. It is also one of the most challenging sounds for a non-native French speaker to produce authentically. There are many ways to go about singing the French r.

Let’s look at the three most commonly used r-sounds in singing French repertoire:

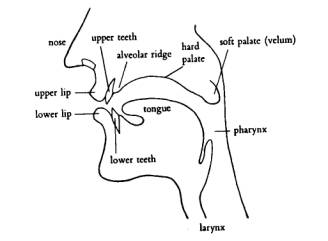

- The “rolled r“: The “rolled r” is also known by its more technical name “alveolar trill”. This is the r we are most familiar with, we use it in all other languages. It is voiced which means you should be able to sustain a sound while rolling the r. The phonetic symbol for this sound is [r]

- The “flipped r“: The “flipped r” is also known as an “alveolar tap or flap”. Very similar to the “rolled r” the flip requires just one brief flick of the tongue to the alveolar ridge. Think of saying the letter d [d]. The phonetic symbols for this vowel sound are [ɾ] or [r], but the latter is the most commonly used.

- The “uvular r”: Also known as the “uvular trill” is the r commonly used in the French spoken language, but also singing. The uvular r is articulated with the back of the tongue (what is known technically as the dorsum) to the uvula (the hangy thing in the back). The difference between the rolled/flipped r and the uvular r is that it is the uvula that vibrates, not the tongue. The phonetic symbol for this sound is [ʀ].

So now that we have listed the three most commonly used r-sounds in French singing, which ones should be used?

Although the “rolled r“ has quite frequently been used in the singing of classical French repertoire, and it feels good to do it (sometimes it may feel expressive to roll an r), my advice is to avoid using it. Whenever I hear someone over-rolling an r in French music be it mélodie or opera, it ends up sounding very close to Italian. Also, any double consonant (except for a few words) should not be observed, so even if you see a double r, you do not need to roll it.

In the following clip, Chanson d’Orkenise from Banalités by Poulenc, Pierre Bernac, who was and still is an authority on singing in French, makes use of the “rolled r” (or one could argue that it is a repeated flipped r). It is still beautiful, but it has a flavor of the past mostly due to the r which is very rolled. This is a good example of how they were singing in French in this period.

The “flipped r” is my personal favorite to use in classical French music. This r is a lot like its rolled counterpart. If you use it while speaking, it feels very strange and foreign but it sounds very comfortable while singing. It does not misplace the voice and it does not disturb the legato line. It is the r most commonly used in French opera and mélodie. In this recording , you hear an excellent use of the “flipped r” used by Véronique Gens.

There are a lot of discussions about the use of the “uvular r“ in classical singing. While speaking French, we all use this r but should we use it when we are singing classical music? In France, Belgium and I believe in the French-speaking regions of Canada, the “uvular r” is recommended for singing in French. From a singing perspective, the argument arises that this places the sound too far back in the throat and that a “flipped r” keeps the sound more forward. In my opinion, the use of the “uvular r” gives a “pop music” feeling to the music. The discussions surrounding which r we should be using are ongoing. My advice is if you are not a native French speaker, do not use the “uvular r” because the chances are you will not make a convincingly authentic “uvular r” sound while singing.

Story time...

I once had a student who was not French, bring in a French aria he had studied all week. Before singing it, he said: “I don’t know why, but every time I sing this aria, I have a sore throat”. Alarmed, I wanted to hear it to see if he was doing anything wrong. It should be noted that this aria was very r heavy. Well, as soon as he started singing, I heard it immediately, he was using his version of the “uvular r”, but it was much too hard and aggressive, we switched to the “flipped r” and everything was solved. We had a good laugh about it afterward!

In this third recording of Chanson d’Orkenise by Poulenc, Patricia Petitbon opts for the “uvular r“. She does it with subtelty and she is gentle with the attack but you can hear that it is in the back of the throat.

My strong advice (and many of my voice teacher colleagues agree) is to use the “flipped r”. Whatever you decide to use, make sure it does not compromise the quality of your singing. Practice now and then with a “uvular r” in case you go off and work with someone who will have this as a preference, and it is requested of you to use it. Work it out with your French coach and your voice teacher to help you to do it healthily and authentically.

The French “h”: What’s the deal?

One of the most frequently asked questions I get during a coaching session on French repertoire is: “What do I do with the “h”? My regular students can recite this rule at any time in any place. It is one of the rules that I drill into them!

The French language went through changes phonologically between it’s origin, Latin, into what we know now as Early Old French. One of the major changes was the loss of the “h” consonant. It briefly made a comeback when germanic words were introduced into the French language, but the aspirate h ceased to be pronounced once more in either the 16th or the 17th century and this hasn’t changed since then.

Since the phonological behavior of aspirate h words cannot be predicted through spelling, usage requires a considerable amount of memorization or a bit of research. In the past, the misuse of the “h” was often used to size up someone’s education and social status. In modern usage, the knowledge of how we treat the “h” in “liaison” is more indicative of formal French, but it is not so present in less guarded speech. In general, the use of “liaison” is also losing ground in the less formal or slang use in the French language all around.

Interesting facts about the “h”

- In all French words that begin with h, the following letter is a vowel.

- Most aspirated-h words are derived from Germanic languages, for example, La haine (hatred) [laǀɛnə] Note: a tiny stop is recommended before the word “haine”

- The h is generally not aspirated in words of Latin and Greek origin, for example, hystérique (hysterical) [histeˈrikə]

- There are numerous exceptions, and etymology often cannot explain them satisfactorily. This makes it very difficult to find a pattern.

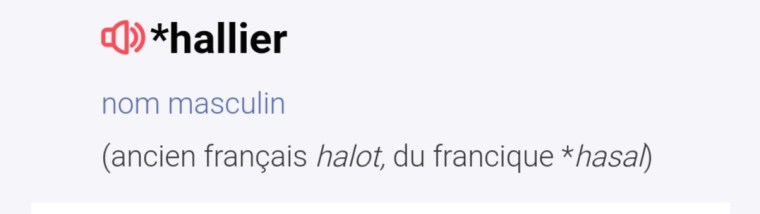

- When in doubt, look it up in a French dictionary. When you do, you will see an asterisk (*) next to the word, and this indicates that the “h” is aspirate.

What is the difference between aspirate and nonaspirate

It is important to note that the “h” is never sounded in the French language, not in speech, and not in singing! So why do we have to know if it is aspirate or nonaspirate? In French, the letter “h” permits or forbids “liaison” furthermore its presence can mean a slight soft reattacking of the vowel-sound.

Example:

Qui dans les halliers humides te cueille! (Who in the damp thickets gather you!)

IPA: [ki dɑ̃ lɛ| aˈliez ͜ yˈmide tə kœjə]

Note that before the word “halliers” there is a slight stop and no liaison because the “h” is an aspirate h. Before the word “humides” there is a liaison because this “h” is nonaspirate.

As stated above, in normal everyday speech, a native French speaker would probably opt out of using a liaison, and most words which are nonaspirate, as they already instinctively recognize them and link them. While singing, however, it is very important to use the appropriate diction. When in doubt, just look it up in the dictionary for the asterisk (*), and remember the rule: It is forbidden to make a liaison on a word beginning with an aspirate “h”!

The French Semi-Consonants

What is a Semi-Consonant?

When you speak (or in our case sing) in French, there are 36 sounds to master:

- 15 vowel-sounds

- 18 consonant-sounds

- 3 semi-consonant sounds (also sometimes called semi-vowels or glides)

In today’s post, we will focus on the semi-consonant-sound.

The Semi-Consonants

Semi-consonant [ɥ]

Model word: nuit [nɥi] (night)

The corresponding sound for the [ɥ] is the phonetic [y] as in the word “lyne” in French

The Yod [j]

Model word: Dieu [djø] (God)

The corresponding sound for the [j] is the phonetic [i] as in the word “midi”. We often refer to this one specifically as a Yod. Think of saying the word “you” in English, that first glide is our [j].

Semi-consonant [w]

Model word soir [swar] (evening)

The corresponding sound for the [w] is the phonetic [u] as in the word “tout”. Think of saying the word “we” in English, the first glide is our [w].

All of the French semi-consonants have these three things in common:

1. They are always before the vowel-sound of the syllable.

In French syllabification, each syllable can only have one vowel-sound per syllable, some vowel combinations make a vowel sound

Example:

- aimer (to love) has two syllables ai/mer. The first “ai” makes one vowel sound and the last “er” make one vowel sound and they are seperated by the “m”

- In the word “nuit” (night), there are two vowel sound and no consonant seperating them, also, there is not combination of “ui” which makes one vowel-sound, so there is no syllabification. The semi-consonant is created: [nɥi]

2. They are introductory closures that open into or glide into the more open vowel sound, which in turn occupies the duration of the note-value.

You should never sing or elongate the semi-consonant, the glide should be made swiftly as you always aim for the vowel following the glide. If we look at the IPA for “nuit” [nɥi] the most important vowel to sing is the [i] which comes after the glide.

3. They never, in themselves, constitute a syllable. When they become vowel-sounds (and/or when they are assigned a note) they lose their qualities as semi-consonants, each being transformed into a particular vowel-sound.

Because we never elongate the semi-consonant, it cannot be a vowel-sound UNLESS they are assigned a note in the text:

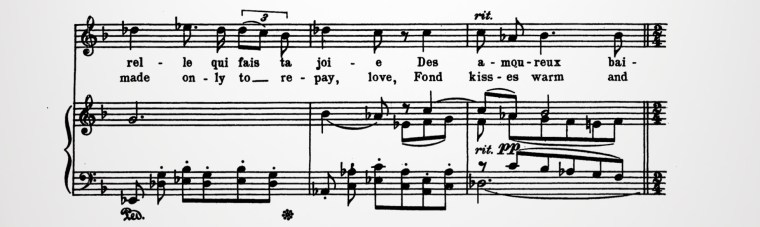

In the example above, the first “curieux” has two notes, and clearly, you would have to use the glide to get to the [ø]. In the second example, the [j] loses its glide quality and becomes a vowel thanks to the composer who gave it a note value.

Be careful not to add a glide when it is not supposed to be there!

In the spoken French language, when a word ends in a vowel + mute “e” (a.k.a schwa), we do not pronounce the schwa.

For example “joie” (joy) is spoken without the last “e” [ʒwa], but many French composers gave a note value to the schwa, so that when you sing the word “joie” you would have to sing this otherwise mute “e” [ʒwaə].

Setting the mute “e” as accurately and elegantly as possible was always a goal for the French composers:

- Setting the mute “e” on the weaker beat

- Setting the mute “e'” on a lower pitch

- Giving the mute “e” a shorter note value than the preceding syllable

- Sometimes suggesting that we drop the mute “e” by setting it on a note tied to the preceding syllable.

- The music determines whether or not we sing the mute “e”

So when you sing the aria “Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle” from Roméo et Juliette by Gounod, you will see the following:

Looking at these two excerpts from the aria, you notice a note value given to the schwas in the words “proie” and “joie”. The danger here is the temptation to insert a [j] between teh [wa] and the [ə].

The correct way to sing this is as follows:

Laisse-là ces oiseaux de proie, Tourterelle qui fais ta joie

[lɛsəˈla sɛz‿waˈzo də ˈproiə turtəˈrɛlə ki fɛ ta ˈʒwaə]

And not

[lɛsəˈla sɛz‿waˈzo də ˈprwajə turtəˈrɛlə ki fɛ ta ˈʒwajə]

Believe it or not, I hear the addition of a Yod quite often, and sometimes from established singers. It is probably not because they mean to do it; gliding cleanly between these vowels takes a lot of practice. Not to mention that if you glide between the vowel and the schwa, you will create a stress on the mute “e” which is not allowed…You have all seen the meme:

Adding a glide between these vowels, creates confusion because it does not sound like the right word, and it is a dead give-away that you are not French. The transition between these vowels must be seemless. Happy gliding!

Make Haste Slowly

“Make haste slowly”

This is what my mentor and teacher, the late Dixie Ross Neill used to repeat to me when I was studying with her, but Caesar Augustus is said to have first adopted the motto: Festina Lente. Make haste, slowly. It took me a while to understand what it meant. I think that when I was a student, I was impatient and maybe a little result-driven. Imagine, back in those days, no social media or profiling trends were pushing me to show my results to the world. Fast forward to 2020, we are the age of social media, instant fame, and being discovered on big platform talent hunts. How does a young aspiring singer get to their desired result while fighting the temptation to skip steps?

I work with singers, and a big part of my work is training young singers who are more than aware of their online content. Knowing how to brand yourself, is an important skill, but the question is, are we skipping important voice building steps in the rush to get “there” faster? Some go into the process, they lay down the base for a great technique, let the voice develop, work on their languages, musicianship skills, bodywork, all of which make someone into a complete artist. Then, there are some who lack patience and are always running after results. They put in the work, but they always try to skip steps because they want to get there faster. With the latter, you can feel an actual sense of panic, which some may confuse with ambition. Skipping steps can make them feel like they are getting there faster, but the truth is, they will inevitably have to turn back and redo the steps they have skipped.

What does it mean to make haste slowly? Let me use the following metaphor: A pianist, while learning a difficult musical passage which is at a high level of technical difficulty is tempted to just play it at tempo, just do it, get it on the first try. There may be a slight chance that they get it right on the first try, but what about every time after that? What will happen to the consistency of their playing? How will they know if it was just a fluke (which it absolutely was)? They now go back, dissect the passage, play it slowly, practice with different rhythms, build up tempo, work on the fingering, and put in the necessary amount of time to learn it from start to finish. Instead of doing it instantaneously and risking that it is just a fluke, the goal now becomes not only to do it right but most importantly, to learn it so that you never do it wrong.

Building your career as a singer is a lot like that pianist working on the difficult passage. Just because you are talented, have a beautiful voice, and sometimes you get it right on the first try, does not mean that you are ready to hit the ground running. Like the pianist working on the passage above, you will want to take the time to establish the foundation on which you build your voice, and that will, in turn help you achieve your artistic and professional goals in the long run. Even if it seems that everyone around you is posting concert photos or doing exciting things; stick to your lane, keep your eyes on your ultimate goal, and eventually you will pass them.

The thing to remember is that we are all learning a craft. Whether you are a pianist, a singer, or any other kind of professional. Knowing everything you can know about what you do is very important. As a young singer I suggest studying where your art comes from, listen to all the great recordings available, examine how the technique and the esthetic have developed over the years. It is a good idea to take note of different styles and conventions of the repertoire so that you can implement them in your singing, or respond to a coach or a conductor when they request them. As you are absorbing all this, also explore listening to all vocal repertoire, not just your voice type, but every voice type, other instruments, and orchestral works. Educate yourself on what you need to know so that once you get out there, you don’t have a lack of knowledge. All this information will most definitely influence your singing and artistry.

As you are doing all of this, be curious and insatiable when it comes to your vocal technique. Whether you are a singer, a pianist, a violinist, or any other musician, technique is the absolute foundation of artistry. Without technique, it is not possible to achieve your musical goals. Imagine doing something incredibly musical: a long phrase, a triple piano on a high note, a lightning-fast coloratura passage, and making it look effortless. Now, imagine that you had the technical knowledge to do this, every-time, without fail. That is what technique means; it is a vehicle for artistic choices. How long does it take to get the technique of a high-level singer? You will probably be working on your technique for the duration of your career, as long as your voice changes with your body. Many of my friends and colleagues with elite careers, still seak help from their voice teachers regularly. When you are a young singer, you lay down the foundation of your technique which hopefully will take you throughout your career. The foundation is the most important part, of course, just think of what happens to a house when the foundation starts failing: it crumbles.

During the spring semester, we were pushed into a different situation in all training programs and education due to Covid-19. We had to go online. It was not ideal, and nobody wanted this, however, I do feel there were good lessons to be learned if you were willing to look for them. The singers that I have heard or seen since have made remarkable vocal progress which in turn has made them much better artists. The focused and meticulous work they did during this time has given them more vocal freedom. They were also free from deadlines and pressures of getting to the result which became somewhat less important for a while. Consequently, they improved quicker than they thought they would. It has been a dreadful time for everyone, but what we can draw from these positive points is that process means progress. In the age of “get there fast”, the part where we slow down to figure things out, is something that most of us have forgotten how to do in this age of “high-speed”. It may take time to get your result, and that is OK. In the words of Caesar Augustus or the great coach and pianist Dixie Ross Neill, “Make haste slowly” and you will get to your result better, stronger, and yes, faster! The quickest way to accomplish something is to proceed deliberately.

How to Sing the French Mixed Vowels

The French language has fifteen vowel-sounds. I say this every year at the start of my French Lyric Diction class as the students’ eyes widen. I can almost hear them thinking “Fifteen? How is that possible? How can I sing fifteen different vowel sounds?” That seems like a lot and it can be quite daunting if you are a singer starting out singing in this language. The three vowel-sounds that I would like to focus on in this little French Lyric Diction post, are the three mixed vowel-sounds [œ] [ø] and [y].

When I say “vowel-sound” I don’t mean a pure vowel. The vowels we all know from when we first learn how to read are a, e, i, o, and u. Think of all the french vowel-sounds as derivatives of these. Some vowel sounds are even based on the derivatives of the derivatives. A mixed vowel is when you take two characteristics of two different vowels and as you combine them you create a whole new vowel. They are called “mixed” because their formation is dependent on the simultaneous positioning of the tongue and the lips.

In the chart above, we see the vowels in the tongue position, and the vowels in the lip position, in the middle are the mixed vowels.

The Phonetic [y] vowel-sound:

- Phonate the [i] sound, as in the French word “midi” [miˈdi] (noon) or if you wish to come from the English language the [i] in the word “we”.

- Now, sustain this [i] sound, as you do so, form your lips to the shape of a closed [o] as in the word “rose” [rozə] in French (or English) all the while not changing your [i] tongue position.

- You now magically have the phonetic [y] vowel as in the French word “lune” [lynə] (moon).

The o-slash vowel:

- Phonate an open [ɛ] as in the French word “tête” [tɛtə] (head) or from the English language, the word “feather”

- Again, sustain this [ɛ] and as you do so, form your lips to the shape of a closed [o] while not changing your tongue position.

- You now are making the sound of [ø] as in the word “feu” [fø] (fire).

The o-e vowel is a little different:

- Start out in the same way you did with the o-slash: phonate on an open [ɛ].

- While sustaining this vowel, you will form your lips into an open [ɔ] as in the French word “homme” [ɔmə] (man) or from the English you can think of the word “on”. So this is less of a closed [o] formation than we used above. (If it starts sounding like [ø], turn back you have gone to far towards a closed vowel with your lips!)

- You now have a perfect o-e vowel, and you can now perfectly sing the word “coeur” [kœr] (heart)

- Nota bene: the Schwa [ə] sound is equivalent to the [œ]. They have the same sound, the difference is that the schwa can never be stressed while the [œ] can be stressed. Example: émeute [eˈmøtə] (riot) while singing this word, the stress is on the o-slash and you would sing the schwa unstressed if it has a note value.

As you sing, if you think about the vowel that you are making with your tongue and just adjust your lips, you can avoid going too far between sounds, and your singing and legato will feel easier, especially depending on the tessitura in which you are singing.

Example:

Intonate these words, all the while keeping your tongue in the [i] position while forming your lips into a closed [o] when reading words with [i] or [y] sounds.

Tu dis qu’il a une fille unique. (You say that he has an only daughter.)

[ty di kil a ynə fij ynikə]

Looking at the phonetic transcription, you have only 2 vowels ([a] and [i]) and two vowel-sounds ([y] and [ə]). The [y] and [i] are the ones you want to practice here. Glide to and from these vowels, see how it feels to not change the tongue position. Try it on different pitches to practice. Do the same with the other mixed-vowels until you master singing them, it will feel easier and your voice will most definitely respond!

Singing in French can be a very scary thing. I am not going to lie to you and tell you that it is easy. But with a few tools, it can definitely be more singer-friendly and as you practice, you will really learn to enjoy singing in this beautiful language.

Choosing Your Vocal Coach-Pianist

Singers, maybe more than anyone else in the performing arts, are bombarded with people giving them their opinion on the way they sing. Everyone seems to have something to say, and they regularly voice their opinion to the singer whether or not the singers wants to hear it. Because singers are not technically able to hear themselves when they sing, it is easy for them to fall into the trap of believing all these opinions. All day long, singers are put in situations where they are set up to receive feedback. The conductor gives them comments, the stage director and/or the stage manager gives them comments, the diction coach gives them comments, the coach gives them comments, the teacher gives them comments, and when they perform, the audience and the critics give them comments. Those are a lot of COMMENTS. This is just a normal day in the life of a singer. It is important for singers to surround themselves with a team of people they trust completely to help them weed through all of the comments and all the outside “noise”. A good coach is a great help in figuring out which feedback is useful.

The coach

What is a pianist-coach? A pianist-coach is a skilled pianist who specializes in vocal coaching. Mostly we know them as coach, opera coach, vocal coach or collaborative pianist. You see your coach regularly, you trust them, you let them see you in the beginning of your process and they stay with you until you are ready to step onto the stage.

There are different types of pianists who specialize in working with singers. You can collaborate musically with a pianist by being both equal partners, you share your musical vision, prepare recitals and recordings together. This is when when the pianist plays the role of a “collaborator” or a “recital partner”. There are also “rehearsal pianists” who you call when you want to run through repertoire without much or any input. You just want to repeat things ad nauseum until you feel ready. Sometimes, a coach can play that role as well, mostly after the preparation is complete and the singer is about to start the job. A coach is not someone who will teach you your notes and rythm. There are pianists who do that, and sometimes singers do need this kind of help, but this is not a coaching, it is more like a practice session, or what is commonly called a “note-bashing” session. Most coaches do not want to do this. “Spoon-feeding” is considered a waste of resources, so don’t just show up expecting your coach to do this. If you are a singer who needs this from your session, you can kindly ask the coach first if they would agree to doing this kind of work, and if they don’t, then ask another pianist you know for a session (often younger pianists or students do this for extra earnings).

When you properly work with a true coach you can expect a more of a teacher-student type of relationship. They provide you with valuable feedback and information. You go to a coach when you want to prepare roles, work on recital repertoire in detail, work on language and text, work on your audition preparation, get to the finer points of character and the music.

Some things to consider when choosing a coach:

- Your relationship with your coach is an intimate one, so most importantly, find a coach that you like as a person. The work you will be doing will be intense. It demands a lot of trust from both sides. You should feel comfortable making mistakes, and they should make you feel comfortable about being corrected.

- Find a coach who meets your skill level. If you are an experienced singer, find a coach who has been working in the field for at least the same amount of time as you have, but preferably they should have more experience.

- When you sing repertoire which is advanced, you want your coach to be able to play it (or at least sight-read it well) and make comments on what you are doing in order for you to improve. If a coach does not know your repertoire, they should not pretend to know it. When I am confronted with unfamiliar repertoire, I am honest about it, I still work on it, but the next time I see the singer, I have learned it. If you are doing something that you suspect is unknown, giving a heads-up is a good idea.

- A coach, should have excellent pianistic skills, they should inspire you to sing and make music, and if you are singing opera, they should be able to conjure up an orchestra from the keys! My favorite compliment is always: “You play like a full orchestra!” This does not mean loud and “bangy”. Playing “like an orchestra” is about the texture of the sound and supporting the singer fully.

- A coach should have quite advanced language skills, they should be able to speak or at least have a firm grasp of the lyric diction in a minimum of four operatic languages: French, English, Italian and German. Their ear should be developed enough to hear even very subtle language inaccuracies.

- Find a coach who understands style and tradition, as well as current trends in performance practice. Whether you bring bel canto, baroque, romantic or contemporary music, your coach is well versed in all of the styles in order to guide you.

- If you are preparing a role, it is of the utmost importance that your coach is able to play the score while singing all the other parts. It does not have to be beautiful singing (trust me!) but it should be audible. If your coach can’t do this, and you have a role coming up, find one who can.

- Your coach is not your voice teacher. A coach can support your vocal technique, but please do not go to a pianist to learn how to sing, or to get vocal technique. This is what a voice teacher is for. Confused? See this previous blog post: A Voice Teacher and a Vocal Coach-Why you need both! A good coach who has years of experience working with singers will be able to point out something that needs technical attention, and then suggest that the singer address the issue with their voice teacher.

- When you work with a coach, they can also be your collaborative partner. If you have musical chemistry with your coach on all levels, then by all means collaborate with them on stage, too!

- It is important that a coach treats you like a person. Yes coaches teach, but you should feel comfortable in your session, not only with the singing, but with making a contribution to the session. A good coach asks questions, wants to know what the singer’s opinion is on the music, text and character, after all, you are the one who is singing it! If you feel like your coaching is a one way street, find a coach who lets you get a word in edgewise.

- The coach you work with makes you feel respected. They are on time and they should not cancel at the last minute (unless it is an emergency…it can happen…but not regularly) and you should do the same for them.

- Look for a coach who has worked with great conductors, organisations, opera houses and singers. They will have first-hand knowledge of what is needed in the world in which you aspire to work. That being said, do not expect that by working with someone attached to a house, that they will get you auditions, work or any kind of exposure to where they work. When singers come to a coaching with the idea that they can get a contact, audition or a job from the coach they are working with, it is very obvious. Believe me, we spot it from a mile away.

- Finally, the coach (or coaches) you choose to work with are accessible, you should feel like you can approach them for advice and have confidence that they will be honest with you. A coach who only tells you what you want to hear is not a coach you need. There is no time to waste and honesty will help you improve, even if it doesn’t always feel great to hear the truth. A good coach will tell you what you need to hear, not necessarily what you want to hear!

Coaching fees-How much should you be paying?

I think every coach needs to come up with a fee that represents what they think their time is worth. Other than the points mentioned above, the following can help you along as you are considering hiring a coach:

- Level of education and/or experience: The longer someone has been working as a coach, the more knowledge they have to share. You are basically paying for their experience and knowledge. As you record your session (always ask first if it is permitted. If not, take tons of notes!), you will be able to refer back to the session for the rest of your life. You will, in turn, most likely use the acquired information in your own teaching and get payed for it yourself in the future!

- Repertoire: With experience, comes a vast knowledge of repertoire. Imagine how many hours the coach in question has spent behind the piano learning repertoire over the years. There is no way they are really breaking even financially!

- Supply and demand: Prices can vary depending on if they are in demand. Some coaches prefer a lower fee and work with many singers, and other coaches like a higher fee and fewer singers.

- The bundle: Some coaches like to bundle, meaning that if you take several sessions, they will give you a lower price. You can ask if they have something like this available where you book a certain amount of coachings ahead of time.

- Student prices: If you study at a school, hopefully they provide a coach, if not, ask about a student fee. Most coaches won’t charge a student the same price as someone already in the profession.

- Online sessions: With the corona-crisis, we are now being more open to the possibility of online coaching. This means that coaches can open up their studios world wide. It is still early days, but maybe there is a different fee depending on what is offered. As the technology develops, we will see how far this can go, but it is an exciting development. It means the planet is a little smaller and you can work with people who are on another continent!

You are paying for advice and expertise and you want the best help you can get in order to do the best you can do. If it feels too expensive, then find someone that is more affordable for you. Ask around and see what the rates are. Every country, city, region has a going rate so answers will vary depending on where you are. I don’t advise haggling on the price of a session. Everyone who offers private coaching has thought long and hard about their fee and it is not customary to try and bargain.

As you go on in your professional career, you can and will work with more than one coach, you can have a list of different coaches for different aspects of what you are working on. Some coaches have specific strenghts that stand out of their vast skill set. When you are a professional singer, you will sing everywhere and have a list of coaches for all the cities where you work-a set of ears you trust everywhere you go!

Online Auditions: Embrace the Learning Curve!

Given our present situation during this global pandemic, we are now forced to look at new ways of auditioning. We can think of this in two different ways: It is unnatural, and difficult or it is an opportunity to learn and create.

I don’t know about you all, but this new world we live in has thrown me into a huge learning curve, which I have decided to embrace. Recently, many conservatories, universities as well as companies have had to move their audition process to an online format combining video and online interviews with potential candidates. It is not how anyone really wants to do an audition, but if we believe the projections, we are all in this situation for what they say will be quite a while. How do we power through and survive?

I put together this little check-list for online auditioning from my experience being involved both in doing them and watching them:

Video and sound quality

The most important part of any audition is how you sound and how you look. Just as in a live audition, there are things which are out of your control, and things that are totally in your control-actually even more so with a video recording! While making some videos with some of my singers, these are important points that we had to consider:

- Set up your video camera at a good distance showing your face clearly with nice lighting. It is not so important to do a full body shot. I prefer to look at your face, and see what you are doing there, so the torso is enough. Lighting can be natural and you don’t have to have all the latest gadgets. Do a test first and see if your face is well lit, not glow in the dark, but clear and warm. You want to look your best and lighting can be a great help! If you are interested you can buy a Selfie Ring Light which is quite affordable and has different light settings, but it is not necessary.

- Your phone video should be good enough, or your iPad or tablet. You want to make sure the sound is as good as possible, so play around with settings. The main concern is distortion in the high notes, you will want clarity of tone but no buzzing. Some phones have these settings, but some don’t. If you can’t seem to control this, I suggest using an extra audio recording device (most singers have this). Your device should have an option to upload tracks to your computer and/or tablet.

- Using your video program like iMovie or Movavi (Windows), you can then add the audio to video by syncing them together. I am a low tech person, so what I found helpful is that before every take someone claps their hands once, and that will serve as a starting point to start synchronizing both video and audio, then everything just falls into place.

- It does not have to be fancy, but try to find a nice neutral background. You don’t want to distract the people you are singing for with a lot of bookshelves, or photos in the background. Most important is that the acoustic is as good as it can be. In these times, most of us are doing this from home. I know it may be tempting to sing in your bathroom, but maybe stick to another location.

- Too much video editing can be distracting to a panel. If you are doing an online performance, then you can go all out, make your own choices, but for a serious audition, keep it simple so we can focus on the beautiful tone of your voice and what you are doing artistically.

- Try not to stare directly into the camera, it is off-putting. Just as in a live audition, too much direct eye contact with your panel can make people feel uncomfortable, the same is true on screen. Find a neutral point by looking at your camera viewer. Do a couple of test shots to see what it looks like. Give the impression that you are looking in our direction and communicating without doing a full stare-down.

- As is form in a live audition, it is a good idea to introduce yourself at the beginning of your clip. It gives a personal touch. However, if you prefer not to, you can just add a title to the clip in our editing program by typing the title of your selection (watch out for tipos…oops, I mean typos!) along with your name and the names of the other musicians who feature in the clip.

- You should pay attention to your attire just as you would for a live audition. Do a couple of test shots, ask your teacher, coach or people you trust to give an honest opinion on the colors you are wearing. Do you look washed out? Do you need more make-up….or less? Are the colors too bright?

- Please make sure you include the pianist or other musicians in the shot. It is considered bad form not to do so, and it just looks odd.

- Finally, you will want to upload your videos for schools or theaters to view onto YouTube. It is easier this way, but do not make them public unless you absolutely want to, and only if you have the agreement of the other musicians featured in the clip. Make the video unlisted. This way the link is easy to share, you just send it via email, and only the people you send it to can see the video, again be sure to add the names of all other musicians to the post and/or video description.

You got through the first round, and now you have an online interview.

So you got through the first round with your excellent video, and the school or organisation wants to speak to you in an online interwiew. Here are a few things to consider:

- Familiarize yourself with the platform which the school is using. This could be Teams, Skype, Whatsapp or what seems to be the most popular, Zoom. You want to be sure how the platform works in order not to have any complications on your side, so a few days before the inteview, experiment with a friend or family member. There could be delays or complications on the panel’s side, and if that happens, just patiently wait.

- Try not to over-dress. Wear something nice, but don’t overdo it. Think buisness-casual. You want to look professional, but not over-the-top.

- Be in a well lit place with a very secure and strong internet connection. Needless to say, busy cafés and such places are not a good idea. Think in the same way as when you recorded your video: natural warm lighting and show your face clearly.

- Be early for your appointment and ready as soon as the panel is ready for you. Just as in a live audition-never make your panel wait! Some platforms have a waiting room, which is great. You just enter and wait until you are let in by the panel.

- Finally, try not to be nervous, act natural and be yourself. It is a weird situation for all involved so just know that everyone is doing their best. Answer the questions to the best of your ability. Have some questions of your own ready, if you get the invitation to do so, ask one or two of them. It is important at this point that the panel has a good feeling about you as a person which will make them want to work with you in the long term. Hard to believe, but this can be achieved on screen!

What happens when you have to sing with a pre recorded track?

When restricitons don’t allow you to work in person with a pianist, you have to get creative. Some people opt for a split screen video: You make a video of yourself singing and the pianist makes a video of themselves playing and you synchronise them. There are many tutorials online showing you how to do this. Another option is to use a pre-recorded audio track and sing with it. Either way, if you are lucky enough to work with someone who wants to make a recording of the piano part for you to use, it is possible to do so and acceptable to use it for an audition. I would suggest to keep the following in mind:

- Have in-depth discussions with the pianist about tempo, rubato, breath as well as the meaning of the text and the mood you wish to convey. You may have to do a few drafts to make sure you have enough space to breathe. You can also try different things, experiment with singing over the phone while the pianist records with your voice in their earphones. Afterwards, you can sing with the recording of the piano for your video recording. The point is, experiment! What I remember seeing were singers struggling to get a breath while singing with pre-recorded tracks, and as a collaborative pianist, that is so hard to watch!

- There are apps that exist like Appcompanist, it is not free and sounds a bit rigid, but you can control rubato, tempo, breaths. You can also find some resources on Youtube, again, you have to try and see what fits best for you. I have noticed that panels are more forgiving of ensemble issues, because of the situation we are in which we find ourselves at the moment.

- Again, as mentionned above, always include the names of your collaborative musicians even if it is a pre-recorded track. I will say from experience, that it takes me quite a lot of work to record one track. Maybe, I am too much of a perfectionnist, but quality takes time, so if you have someone on your team who will do this with you, that is just amazing!

As singers, this is a very different and difficult situation because you need someone else to play with you in order to do your job and unfortunately in this time, this is not always possible. Auditioning online is daunting, and unnatural, but it doesn’t have to feel too rigid or difficult. Be prepared, do your homework and test it out first. Remember to show yourself at your best and don’t be afraid to try new things, you never know what is waiting for you on the other side!

When Does a Nasal Vowel Lose its Nasalization?

If you have taken any French diction course in your life, you know that in French there are 36 sounds to master and 15 of them are vowel sounds (and then you have 18 consonant sounds and 3 semi-consonant sounds). The most misunderstood of all French sounds is the “nasal” vowel sound. In the French language there are four:

- [ɑ̃] which is based on the french “dark a” sound as in the word “âme” (which means soul)

- [õ] which is based on a “closed o” sound like in the word “hôtel” (which means hotel)

- [ɛ̃] which is based on an “open ɛ” sound like in the word “mais” (which means but)

- [œ̃] which is based on the “o e” sound like in the word “chacun” (which means each)

When I say it is “based on”, I mean that the basic vowel takes up approximately 85 -90 percent of the nasal sound, depending on tessitura, and the rest is resonance which passes through the cavities that are found near the nose, in the yawn space, more or less in the center of your head, but not in your nose.

The reason a nasal vowel is called as such is because the consonants which follow the vowel in question are the nasal consonants n and m. In order to produce these consonants, you must pass through your nasal cavity. That being said, you should not pronounce the m or n in a nasal sound unless it is in a “liaison*”. The combination of a vowel plus the nasal consonant is why they are known as “nasal vowels” and not because they belong in your nose. The m or n that follows every nasalized vowel-letter is silent. A nasal vowel is just that, a vowel. It is not a vowel-plus-a-consonant, a sort of m or n, or the faint “ng” sound which is nonexistent in French.

While singing, if someone wishes to sound “as authentic as possible”, they tend to over-nasalize the French nasal sound which results in a much less resonant sound-actually it can cut your sound in half leaving you feeling stuck. Thinking of the appropriate basic vowel, and focusing your attention on it while letting the resonance take care of the rest, will be more conducive to proper singing and will sound much less stiff to the listener whereas exaggerated over nasalization sounds a bit comical.

Now that we have had a brief look at how a nasal vowel functions, when does the vowel loose it’s nasalization?

Rule: Any vowel-letter(s) followed by m or n is usually nasalized unless the m or n is followed by:

1. a vowel-letter or a vowel sound in the same word.

Example:

immense (which means immense) [imˈɑ̃sə]. The double “m” takes away the nasal.

or

2. an m, n, or h in the same word.

Example:

bonheur (happiness) [bɔˈnœr]. Although the word “bon” is most definetly nasalized, the word “bonheur” is not.

So whereas the vowel-sound of the word “sein” [sɛ̃] (meaning breast) is nasalized the name of the river flowing through Paris, the ‘Seine’ [sɛnə], is not, since the n is followed by a vowel-letter.

Denasalization usually does not occur between words or words in liaison: mon amour (my love) [mõn ͜ amur] As you can see, even if the n is pronouonced because it is in liaison, the o stays nasalized.

Exception:

In these following instances, the nasal vowel stays intact even if the m or n is followed by another m or n:

emmener (to bring) [ɑ̃məˈne]-this word has a double m, but the nasal remains.

ennui (boredom) [ɑ̃ˈnɥi]-this word has a double n, but the nasal remains.

And remember what I said about this rule does not apply in liaison? There is an exception to that too (as there are exceptions to most French diction rules):

When you wish someone “Happy Birthday” in French, you say: “Bon anniversaire!”. The correct way to pronounce this is [bɔn ͜ anivɛrˈsair(ə)], without nasalization on the o or the a, but I notice that the pronunciation of this saying confuses the orthography and it is often wrongly spelled: bonne anniversaire. This of course cannot be, because “bonne” is the feminin form of the adjective “bon” and “anniversaire” is a masulin noun. So, we speak it one way, but it is written another way.

So the next time you want to write a message on your French friend’s social media, you can write “Bon anniversaire!” and you will know why we pronounce it differently than how it looks!🎂

*liaison: A liaison may occur only between a normally silent final consonant and an following vowel-sound. Ex: les ͜ amoureux (the lovers) [lɛz͜͜ ͜ amurø]

You must be logged in to post a comment.