After years of coaching French repertoire, I have come across some difficult words which people struggle to pronounce, unless you know how to say them. There is no way to figure them out unless you are a native speaker. Pronouncing these words cannot be solved with diction rules or IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet). Let’s look at three of these particular words and some contexts where you can find them.

Solennel

The word Solennel meaning Solemn in English, is often used in French poetry. It looks like we pronounce it a certain way, but it is not what you think. Let’s dissect this word:

If we use our knowledge of French diction rules, it may look like we pronounce it as [sɔlɛˈnɛl]. If we are unaware that nasal vowel sounds when followed by another n loses the nasal quality and returns to its original sound (for more on this rule, see my previous blog post), the temptation is to add an [ɑ̃] in there to cover all of your bases.

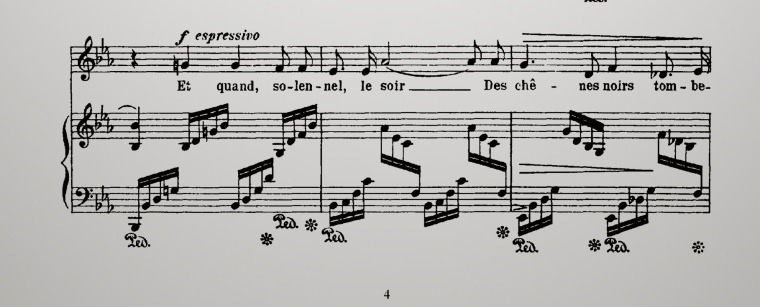

However, this would be the wrong way to say this word. In the following excerpt from Fauré’s Cinque mélodies de Venise we find this word in “Et quand, solennel, le soir…”

We pronounce the text as follows: [e kɑ̃ sɔlaˈnɛl lœ swar]

Yes, you saw it correctly; that is an [a] in there. This word has gone through some spelling changes over time, which is why you sometimes still (although rarely) see it spelled solemnel. Even with this older spelling, the word is still pronounced [ sɔlaˈnɛl]. In the following clip, you can hear its correct pronunciation at 2’10”:

Femme:

The word femme, meaning woman, is also one of these abnormal words which looks one way and sounds another way! When we pronounce the word in English as it is written in French when we use expressions such as “Femme Fatale”, which can sound like “fem fuh·taal“, but beware, this is not how this word sounds in French! In the following example from Fauré’s Rencontre, we find this word in the text: “Ô dis-moi, serais-tu la femme inespérée…”

We pronounce the text as follows: [o di mwa səˈrɛ ty la fam͜ inespeˈreə]

The word femme is also pronounced with an [a], as you will hear in the following clip at 18 seconds into the recording:

The Verb Faire:

Commonly mispronounced, the verb faire , meaning “to do” in English, also happens to be one of the most common verbs used in the French language and poetry. There is also a particular pronunciation of the root of the verb in some conjugated forms.

For example, in most tenses of the verb, the -ai- component of the word is pronounced as an open [ɛ] as one would expect. The spelling also totally changes in some of the rarely used tenses, and there is even no root word “fai” anymore. Regarding the -ai- sounding utterly different than what it looks like, here is a list:

PRESENT: je fais [fɛ] tu fais [fɛ] il/elle fait [fɛ] nous faisons [fœˈzõ]

vous faites [fɛtə]

ils/elles font [fõ]

IMPERFECT: je faisais [fœˈzɛ] tu faisais [fœˈzɛ] il/elle faisait [fœˈzɛ] nous faisions [fœˈzjõ] vous faisiez [fœˈzje ]

ils/elles faisaient [fœˈz ɛ ]

Notice that in the first person plural of the present tense and all of the imperfect conjugation, the verb’s -ai- sounds like [œ].

In the following text from Duparc’s La vie antérieure we find the text: “Le secret douloureux qui me faisait languir” we see two -ai- syllables, and one could assume that they sound the same, but this is the imperfect form of the verb “faire”..

We pronounce the text as follows: [lə səˈkrɛ duluˈrø ki me fœˈzɛ lɑ̃ˈgir]

You can hear it clearly in the following clip at 3’19”:

Eut

Yes, this is a word. In this case, it is a verb. If you have followed any French diction course, you should know that -eu- when it is the last sound in a word sounds as an o-slash [ø] unless the -eu- in question is part of the verb avoir (to have). When it is part of this verb, it sounds very different.

It can be in this form of the verb with an auxiliary:

J’ai eu (I have had) or in this form il eut (he had). It will still sound the same:

J’ai eu (I have had) [ʒe y]

Il eut (he had) [il y]

I have heard this word often turned into an [ø] or even an [œ]. When you translate your text, be sure to be alert and if it is a verb, use the appropriate pronunciation.

In the following clip, you can hear the proper way to sing this sound at 1’58”:

Véronique Gens and Roger Vignoles

A thing that I repeat to my non-native French-speaking students all the time is: “When pronouncing French, please don’t trust your instincts because they are probably incorrect. Stick to the rules and what you don’t know, ask a qualified French diction coach”. There are more words like the ones I have mentioned in this post, but these come back mispronounced, again and again, so memorize them, and you will be ahead of the curve!

You must be logged in to post a comment.